Predictions are extraordinarily difficult; particularly when they’re about the future! I drew this tongue-in-cheek conclusion in my PhD dissertation. But I wasn’t attempting to be funny. I was making the point that in spite of the near impossibility of making such predictions, daily we are overwhelmed with opinions published by futurists, geopolitical analysts, and countless self-proclaimed experts.

There was a sentence that I used to routinely put in my notes on my students’ essays, when I found them lacking: You are entitled to your opinions, whatever they may be. But I wasn’t asking for your opinion. I was asking for your fact-based argument. Fact-based arguments appear to be a diminishing commodity in this century.

Let’s look at why we cannot predict with any accuracy what the world geopolitical order will look like beyond the next ten or fifteen minutes. To begin, we should sweep away any notions that we have of balance of power international political systems. Although this is a well-established concept in geopolitics, in my opinion it is a deeply flawed analogy. If we must use an analogy, then I would suggest that rather than a balance that we use a model based on what Henry Kissinger called an equilibrium of power. In other words, do not think of a scale or a teeter-totter. Think of a multicoloured disc spinning on a needlepoint where each coloured slice of pie on the disc represents a country and/or its power/interests. It only takes a moment to realize that Kissinger’s model is much more complex and that it is highly dynamic. Those two reasons are why I think it’s a better model for us.

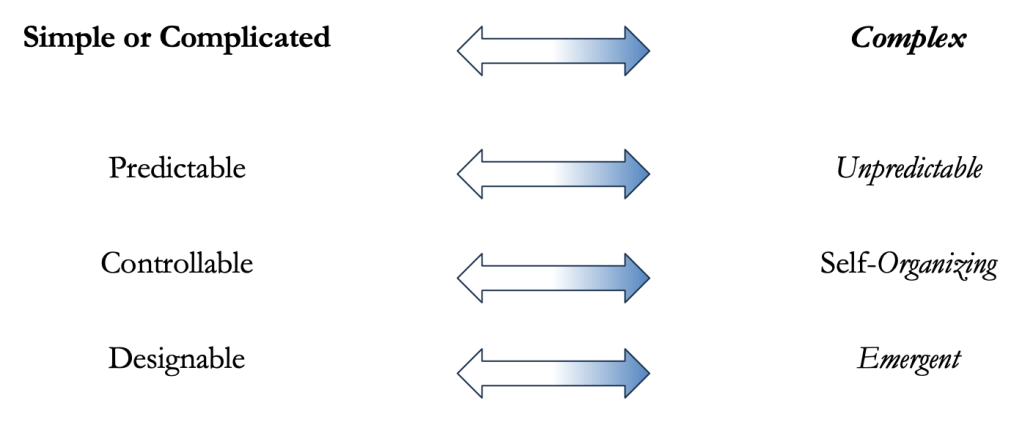

Next, let’s consider that too often we think of geopolitics as being highly complicated. That is false. They are not complicated at all; they are complex. Look below and you’ll see why it’s important to appreciate the distinction (which is often overlooked).

This is an easy mistake to make and in most conversation, it may not really matter. But when we consider geopolitical situations and scenarios, we must make the distinction. Doing so at the outset immediately puts us in the correct frame of mind. Although we may presume that certain situations will follow the path they are currently on, appreciating the difference between complication and complexity constrains us from further presuming any predictability. As the model above reminds us, complex systems are unpredictable.

So, is there any point in attempting to look forward along the arrow of time to attempt to see what might happen? The cynic may say no, but the realist says yes. We have little choice. Not to anticipate potential outcomes is irresponsible. But there is a correct way to do so and an incorrect way.

Time to shift to military-speak. In military operations we use the concept of branches and sequels. In simple terms a branch is a contingency or option that is already part of an existing plan. A sequel is an operation based on a possible outcome of an existing plan. In other words, if something happens and you had foreseen the possibility, you alter course and move onto that branch. If you are moving toward your goal and achieve what you had hoped, you then choose a sequel to continue what you are doing. In either case, you are obliged to cast your thinking forward and consider multiple options — realizing that you may do an immense amount of work in creating multiple branches and sequels, only to be surprised that something completely unexpected occurs. As we all know, life is what happens while we’re making plans.

As usual, allow me to link military thinking with what I’ve been blathering on about. Many people like to quote Prince Otto von Bismarck, the man who literally forged (Blood and Iron) modern Germany out of the handful of duchies and principalities of the German Confederation in 1871. He famously said to a Russian journalist that “Politics is the art of the possible.” That is the common English translation, but when one looks at the German quotation and understand it in Bismarck’s military strategy in a geopolitical context, the meaning changes. “Die Politik ist die Lehre vom Möglichen.” This is a better sense of what the Iron Chancellor meant: “Politics is the doctrine of the possible, of the attainable … the art of the next best.”

Bismarck’s deep understanding of the relationship between politics and military action frequently brought him into conflict with the General Staff, which usually saw politics as an encumbrance to their desire to crush enemy forces, even if the political consequences hurt the ultimate national objectives. Just because all of these men had read the work of Carl von Clausewitz, did not mean that they all understood them.

Clausewitz’s ideas are not complicated; they are complex.

I would go further and describe the world geopolitical system as a Complex Adaptive System (CAS) that exists in a form of dynamic equilibrium. It is in no way static. The blocs in the world are subsystems, as are the nation-states in those blocs. The nation-states can (and often do) belong to more than one bloc. This means that they can have an effect on more than one bloc, and those effects will cascade through the CAS due to all the connections – whether they be political, economic, or personal.

We could have a very interesting discussion on this sometime.

Rory

LikeLike

I like the analogy. It works.

LikeLike