When public figures attempt to explain what they are doing, they often look to historical examples to prop up their arguments, especially when those arguments are weak. There is an obvious risk with this tactic. If you do not understand the lesson of the history you cite, then calling upon the ghosts of the past as a pretext for your actions just makes you look idiotic. This is especially true if it comes to using military history.

There are two recent examples that illustrate this process and they involved the lax use of mid 19th terms like Realpolitik and Monroe Doctrine. The former refers Reichkanzler Otto von Bismarck’s statecraft and the latter to James Monroe’s doctrine. Let’s look at them in turn.

Prinz von Bismarck is arguably the most famous historical figure to be associated with the concept of Realpolitik, a philosophy that emphasizes practicality over ideology. Utility over morality. Using this philosophy as his starting point, he employed his ruthless methodology of ‘Blood and Iron’ (Blut und Eisen) to unify German states under the Prussian crown in the 1871, pushing the discordant states to crown Wilhelm as the first Kaiser of Greater Germany. Bismarck’s relentless prioritizing of national interest, power, and flexible diplomacy won out over all other considerations — sometimes putting him at odds with the Prussian military, as it did when he would not allow Helmuth von Moltke the Elder to destroy the Austrian Army in 1866.

Bismarck was a master of strategic manipulation, diplomatic balance, and domestic control. His now famous dictum that “Politics is the art of the possible” encapsulated the true essence of Realpolitik. Leaders had to adapt their policies to circumstances, make difficult trade-offs, and pursue achievable results.

Realpolitik remains a defining model in international relations, but in the process is too often misunderstood. Citing the classic phrase “The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must” a famous phrase from the Melian Dialogue in Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, where strategic interest overrode moral principles (as the current Gold House does) proves the point: Athens destroyed itself in the process of “demonstrating” that it was a hegemon and could therefore do what it pleased.

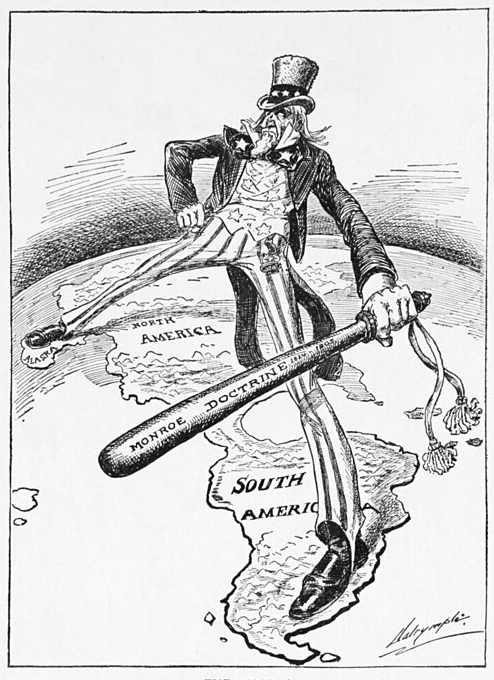

In 1823, President James Monroe, in his State of the Union Adress, first iterated this keystone element of U.S foreign policy: leave America to the Americans. But the doctrine is often misunderstood. The Monroe Doctrine warned the European imperial powers not to interfere in the affairs of the Western Hemisphere. Contrary to what many think, America was not saying that it wanted all of the hemisphere for itself; it was stating that it did not want to see any form of colonization or puppet monarchies established in the Americas backed by a European power.

The misinterpretation may be subtle, but important and came about largely due to a 1902 European interference in Venezuela (sound familiar?) due to their financial default. It was President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1904, “Roosevelt Corollary” that was the trigger. Roosevelt claimed that Washington had the right to intervene in the hemisphere whenever necessary. It was America’s responsibility to protect the other countries and preserve the order of the continent. And there’s the rub. What defines necessity?

Although initially conceived as a warning to European imperialists, the Monroe Doctrine shifted in 1904 to be interpreted as America giving itself the rights that it had denied the Europeans. As with all acts of hubris, this interpretation contained the seeds of its own destruction, if allowed to take root (I would suggest that the current US administration re-read Thucydides, but I am not aware of a cartoon version of that tome, and so will keep my powder dry.)

Maduro posed no direct threat to America, as did Cuba did in the early 1960s, when the Soviet Union’s missiles were a direct provocation. Venezuela did not and does not have a comparable situation.

To sum up, history, like war, offers many lessons. But like war, there is a distinct difference between lessons offered or observed, and lessons learned. Santayana’s admonition regarding reliving mistakes of the past — whether from the Peloponnese or from the Caribbean — comes once more to mind.

Political cartoon by American Louis Dalrymple (1866-1905)