To an uninformed observer, the concept of winning a war or losing a war may seem straightforward. But war is not a board game like monopoly or checkers. Winning and losing are binary concepts that too often do not adequately describe what is happening in an armed conflict, whether it’s in a Russian oblast or a disputed Middle Eastern territory.

A frequent question in many interviews lately is “Who’s winning the Russo-Ukraine War?” The simple answer is “nobody”, but that answer is not useful, so let’s dig deeper.

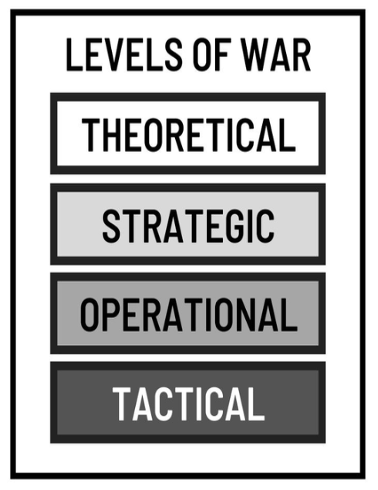

To better understand the circumstances surrounding the question, we need to quickly review some military theory (I can hear you groaning). War is physically fought on at least three levels: tactical, operational, and strategic. I have always maintained that there is a fourth level that we need to appreciate, though it is not a physical one. The fourth level is the theoretical level, and it undergirds the previous three; it sets the conditions for understanding whether a side is “winning” or “losing”. Here is the simplified model I have used to teach this concept (from my book Strategia):

Where the theoretical level becomes important is in determining whether the belligerents share an understanding of what is occurring. A modest example would be the American Civil War (or if you live in the Deep South, the War of Northern Aggression.) When we apply the above model to that conflict, we can safely ignore the theoretical level because all of the leaders, both civil and military, shared a common understanding of how that war was to be fought. Not surprising since most of them attended the same school, the US Military Academy. But let’s dig deeper.

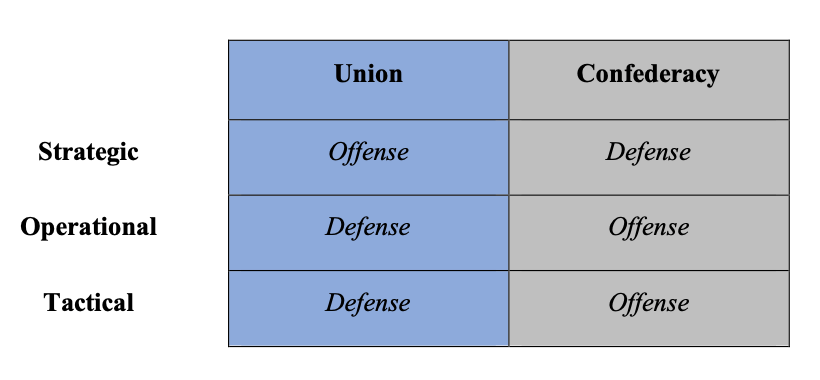

Consider the American Civil War in classic Clausewitzian terms. The offense is decisive, but the defense is the stronger form. The North had to decisively beat the South and make them sue for peace. Any result short of that would be a victory for the South. In other words, the South did not have to defeat the North, they needed merely not to lose. Thus, the North was on the strategic offensive, while the South was on the strategic defensive. Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee created their strategies based on this seeming paradox, which is one explanation for why Robert E. Lee — arguably the best battle commander in the war, launched what in hindsight seems like a suicidal frontal attack at Gettysburg. Consider the matrix below. It’s a snapshot of the two opposing armies on the morning of 30 June 1863. They were about to meet each other near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

The Union, at this time not yet working with the winning strategy created later by Ulysses S. Grant, was on the strategic offensive, even if some of its senior generals were on the defensive with their Corps and Divisions. The Confederacy, knowing that it did not have the resources for a prolonged war, was on the strategic defensive. But Robert E. Lee, knowing that he had to take the war to the North’s doorstep and defeat the Union armies on the battlefield, was on the operational as well as the tactical offensive.

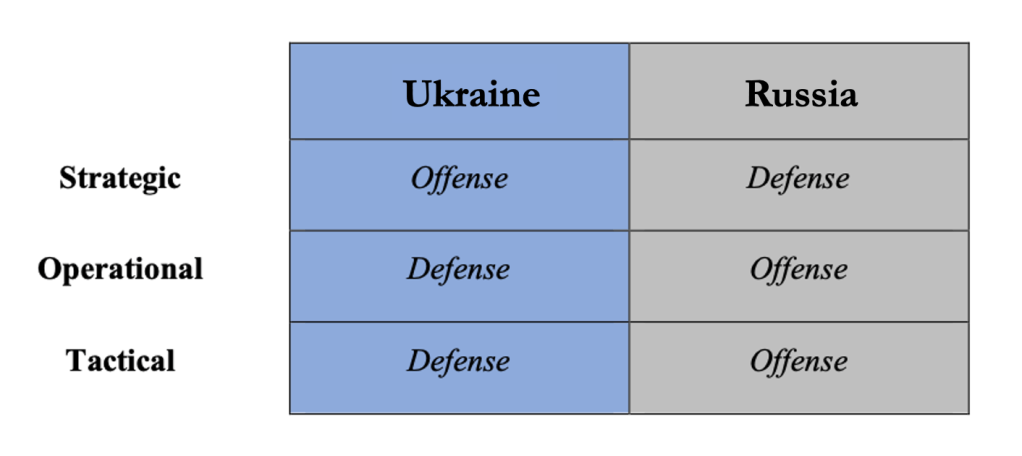

Take a moment and let that sink in. Now apply it to the Russo-Ukrainian War. Do both sides share a theoretical understanding of war? I do not believe they do. There isn’t room here to go into why I think that, so maybe you can just trust me (or challenge me in a comment on my web page, where I can engage those interested). What about the three physical planes?

At this time, I believe the matrix above adequately describes what is going on. Ukraine has successfully turned the tables on its invader and is using a limited form of airpower to strike at strategic nodes (see the work of Colonel John Warden, USAF) in a purely offensive manner and is on the path to cripple Russia’s wartime economy. Russia has proven incapable of a strategic offensive although it continues to be on the offense at the operational and tactical levels.

In my Part II, I’ll explain how these levels mesh with the Clausewitz’s “wondrous trinity” (wunderliche Dreifaltigkeit) but for the moment, let’s return briefly to the theoretical level and appreciate that for Ukraine the war is existential, and must therefore be won. For Russia, losing would be a severe blow but unlikely to cause the country to cease to exist. Whether these conditions apply to the two national presidents is a question for another post.

So, the question remains moot. Who’s winning? We’ll look at that in Part II …